You’ve all seen the news. Pictures of an enormous container ship blocking the Suez Canal has dominated the news for the past fortnight. And that’s to say nothing of the countless memes.

But what was that actually all about? And what does it say about supply chain resilience? Let’s take a look.

On the 23rd March one of the world’s largest ships – The Ever Given – carrying 18,300 containers, was thrown off course by a sandstorm whilst passing through the Suez Canal. To demonstrate exactly how big the ship is, she measures 399.94 metres long and 59 metres wide. That’s longer than the length of the Empire State Building from ground to tip!

Reports suggest that the Ever Given’s weight at the time of grounding was about 220,000 tonnes. To give some context, that’s the weight of about 44,000 African elephants. The ship is operated by Taiwan’s Evergreen Marine, and sails under the Panama flag.

How did the Ever Given get stuck?

The ship became lodged in the canal at a sharp angle, supposedly due to high winds that blew it off course on its way through the Suez canal. As the ship is so long it became firmly stuck to the banks at both sides of the canal, completely blocking the route. The margin for error is very small with such a large ship, and even with a very quick reaction it takes a long time to be able to manoeuvre the ship.

What’s all the fuss about?

The Suez Canal in Egypt sees 10% of the world’s trade flows pass through it; an estimated $9.6bn of goods, on more than 50 ships, each day. It stretches from the Red Sea and the Mediterranean, and at 120 miles is the shortest route from Asia to Europe which makes it a highly popular passage for container ships, dry bulk carriers and tankers. It is also used as a key route for oil tankers passing to and from the Middle East. As such an integral stretch of water to international trade, the Suez’s blockage had an enormous impact.

With more than 360 ships being held up by the blockage, some were forced to accept a 12-day diversion around the Cape of Good Hope – a very long diversion all the way to the other end of the African continent that costs more than $26,000 a day in fuel costs.

How did the Ever Given get free?

The situation was looking pretty dire, with the potential to last for weeks. The blockage lasted for six days and saw salvage companies work tirelessly, night and day, to re-float the enormous vessel. Work was done to dredge sand from the bank and bed of the canal and use ordinary tugboats to try to shift the ship, seeing Egyptian, Dutch and Japanese salvage teams work on land and water for six days and nights. Work was also done to unload some of the ship’s cargo, to lighten the load and make the dislodging easier and the teams managed to move 30,000 cubic metres of sand over the course of the week.

Ultimately, salvage teams were assisted by two larger tugboats able to assist. Until these arrived, dredging sand wasn’t making much impact on its own. The first tugboat, the Alp Guardis, is capable of pulling 285 metric tonnes – 75% more than the canal’s fleet of tugboats can manage combined. It managed to shift the Ever Given’s stern, which could then act as a lever to free the rest of the boat. When the second powerful tugboat, the Carlo Magno, arrived they worked to clear the bow. They had to calculate exactly where to place the tugs in order to make maximum use of the tide.

The biggest helper though was the moon, which due to its being full on the weekend changed the tide to a level that enabled the Ever Given to once more take float. By noon on Monday 30th April, the high spring tide was able to allow the ship to make a move. Once the boat was free, there was plenty of chanting and celebration.

What was the impact on global trade?

The blockage cost global trade an estimated six to ten billion dollars a day. In the short term, the blockage also added strength to otherwise weakening oil prices, amid concerns that global supply could be impacted. About 600,000 barrels of crude oil are shipped from the Middle East to Europe and the United States, and 850,000 barrels from the Atlantic Basin to Asia each day via the Suez Canal. However, there are alternative routes for tankers which, unlike the Ever Given, can travel in smaller passages of water such as the Sumed pipeline.

Despite being freed this week, the blockage caused by the Ever Given is predicted to cause further disruptive shockwaves to global trade, though experts disagree about exactly how much disruption will be caused. Other ports and deliveries will be impacted by the re-routing of other vessels, as well as the domino effect these delays will have on sailings booked for the coming weeks. Freight prices have been high for the past few months as a result of rebounding supply and demand after pandemic-induced lows. With more pressure in the market, this could continue.

The timing was also important. The blockage happened at a particularly unhelpful time in the calendar year – right after Chinese New Year which sees factories close, creating more urgency for the goods travelling at that time. All of this further exacerbates pressure from a container shortage caused by Covid-19, and covid safety rules that are making loading and unloading slower then usual at the moment.

Ultimately, this is one of the challenges of a just-in-time delivery system. If part of the large web of precise movements and timings is out of place, a ripple effect is felt along the entire industry. Containerised products are often quite specific by comparison with bulk products such as oil that can be substituted for other sources.

This means that there is likely to be a continued shortage of specific products as a result of the blockage. For example, if car parts do not arrive, assembly lines halt. Ships holding livestock also face challenges as the animals are on board for longer than intended which poses health risks, and grains or other foodstuffs are also time sensitive, and at risk of passing their use by date. Medical goods are also shipped in containers, posing threats to supply.

When is big too big?

Growing preferences for fast deliveries and low-cost goods have created an upsurge in the amount of large vessels at sea which can handle large volumes of goods. However, one thing can’t be changed: the layout of the planet. These ships are only able to access a limited number of ports, creating an overloaded and pressurised shipping route system.

The route from China to Rotterdam, which the Ever Given was on, is often used for larger ships, as their containers can be offloaded at Rotterdam and transferred to smaller boats capable of travelling more nimbly around the rest of Europe, or to the United States. Because of this trend, backlogs created by the blockage will lead to further pressure on these ports.

Is this going to keep happening?

It’s worth noting that the Suez has been blocked before, five times according to the Suez Canal Authority, though none have lasted as long as this recent blockage. According to shipping specialist Lloyd’s List Intelligence, 114 similar-sized ships have made the same journey as the Ever Given in 2021 already and passed through the Suez successfully.

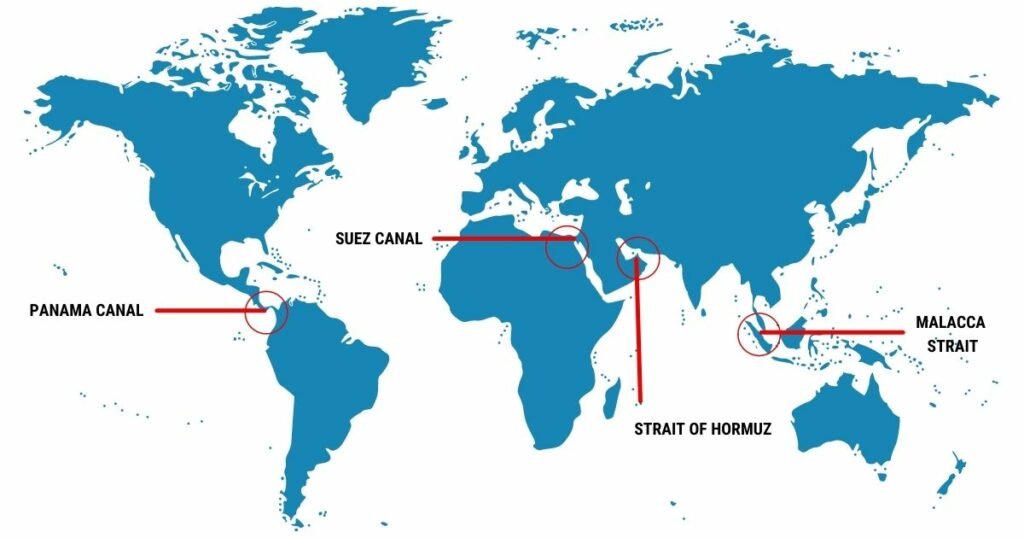

That said, there are four key ‘chokepoints’ globally that are vulnerable to blockages of this type. They are:

The Suez Canal

Where: The Suez canal is in Egypt, and connects the Red Sea to the Mediterranean.

Length: 120 miles

Significance: The Suez Canal is important because it is the shortest maritime route from Europe to Asia. The canal revolutionised shipping routes because prior to its construction, ships headed toward Asia had to embark on an arduous journey around the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa. Constructed by France and Egypt, the Suez was the designated ‘neutral’ passage for trade from all nations, although this invitation was only stretched to the largest European powers of the era.

Panama Canal

Where: It connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans through a passage in Panama.

Length: 50 miles

Significance: Historically, it has handled 5% of world trade but as a narrow channel was limited. In 2016, it opened an expansion which tripled the size of ships that could pass through, allowing them to avoid the hazardous journey around Cape Horn.

The Strait of Hormuz

Where: This is a sea passage between the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, and a critical route for oil and gas. It is vulnerable to geopolitical tensions as it connects many key players in the oil market including Saudi Arabia, Iran, The United Arab Emirates, Kuwait and Iraq.

Length: 90 miles

Significance: it sees about a quarter of the world’s seaborne-traded oil and and a third of the world’s liquefied natural gas pass through.

Malacca Straight

Where: The passage links Asia with the Middle East and Europe

Length: 559 miles

Significance: it carries about 40% of all global trade each year and is one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes.

Whether this keeps happening is down to how much pressure is going to be placed on these routes in future, and how technology on ships might develop to avoid human or weather-induced errors.

Building resilience

Advancing technology and the impact of COVID-19 has already caused a sharp increase in the focus on and development of supply chain resilience. By this term, we mean the ability for supply chains to keep moving amongst disruptions to the global trade environment. Already, manufacturers are making their processes more localised and mobile, and continued reductions to the size of goods (for example flat screen TVs) and digitisation of books and media reduce the amount of containerised goods moving around the world.

Czarnikow’s logistics service is built upon an ethos of flexibility, resilience and innovation, allowing us to help you keep supply and demand in balance. You can find out more about how we can help here.

Images: New York Times, William Watcher on Unsplash